NOTE: This work was a prototype as we don't have yet an official roadmap and timetable in mind to bring this to Unity, more on that later this year hopefully ;)

This blog post is also my own opinionated vision on the subject, but Unity may have different plans and constraints across the teams involved on this. So it may not be the direction Unity will take in the end!

NOTE about IL2CPP: Even if Unity could use a dedicated GC aware codegen like CoreCLR/CoreRT for some platforms, IL2CPP is and will remain the best option to quickly target and support new platforms (or even very old platforms). Only once we could generate GC aware codegen for this platform then we could switch to a more suitable option. This post is really not about replacing IL2CPP but about providing new optimization opportunities for some targeted platforms.

Every year Unity organize a coding week event called #HackWeek during which R&D developers at Unity are invited to spend a week to unleash their imagination with passion, and work on something they would love to bring to the Unity platform (or to work on, or to just open their mind to different domains/skills... etc.). It is also a great opportunity to meet other coders there and to work on something else. It reminded me a bit the demo-scene coding parties, without the ranking at the end - the continuous music around, or the crowd shouting "Amiggaaaaaaa"... but in the end, a very similar amazing experience! ;)

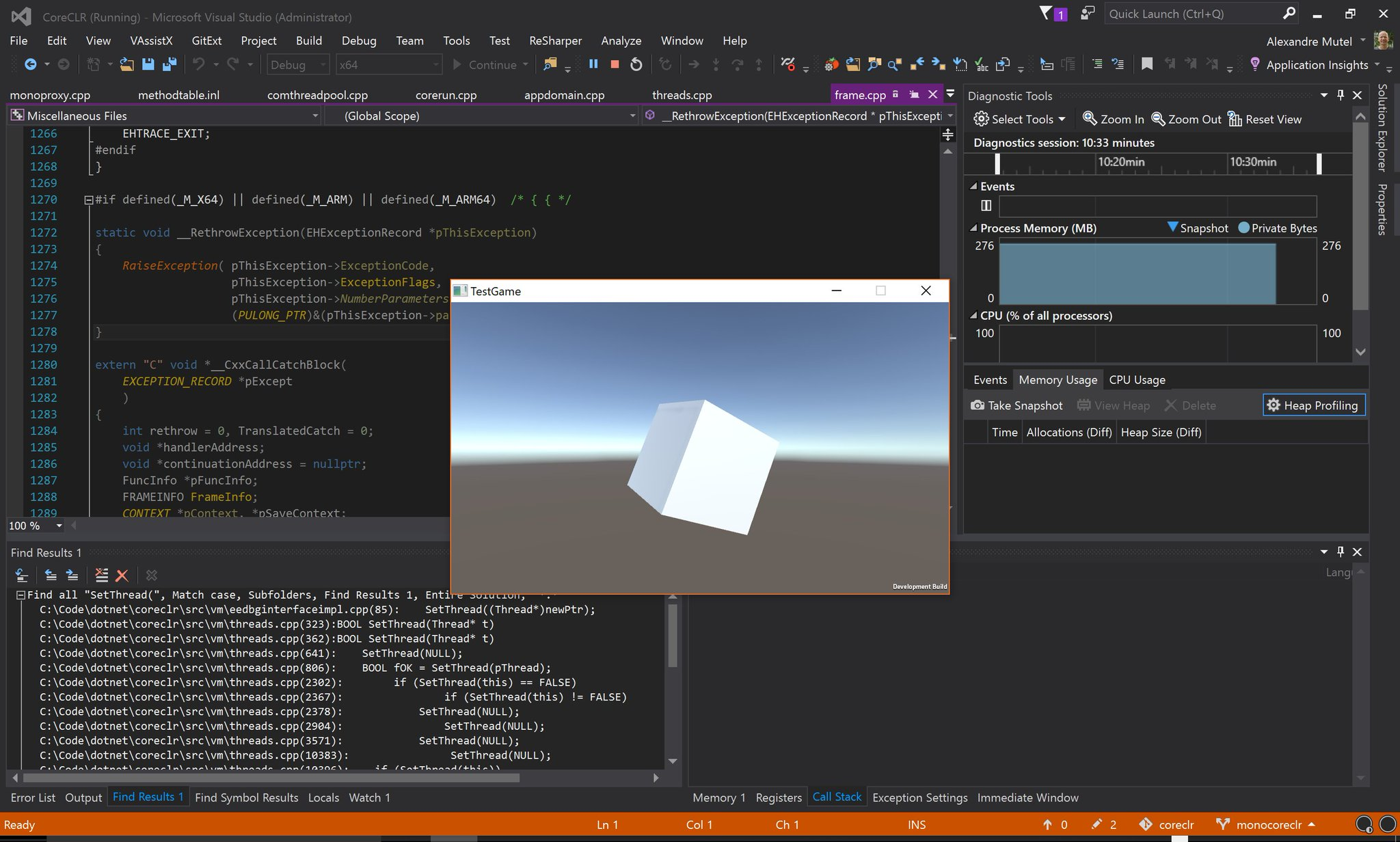

During this full HackWeek of work opportunity in May 2017, I decided to try to port the Unity Engine to the .NET Core platform and I was happy to welcome 3 other developers to challenge this idea. For many observers, the general feeling was that it would be barely possible to achieve this in one week but I was - cautiously - optimistic about this. It turns out that we were able to run a simple Unity player with a spinning cube, on both Windows and Mac! While sounding quite a limited result, this was a significant achievement, and we were all delighted to get that far.

This post (my apologize for not writing it earlier!) is going to give more details about the work involved, why .NET CoreCLR?, how we did it? and why this is in my opinion, an important step for the future of Unity...

Unity and the .NET platforms

Unity is currently supporting roughly 3 .NET platforms (with some variants inside them):

- Mono, for the Editor and StandalonePlayers on Windows, Mac... This platform is the original .NET runtime that has been used by Unity since its early versions.

- IL2CPP, by translating IL to C++, originally developed to support the iOS platform, but expanding fast to other platforms

- WinRT .NET, to support the more restricted Windows Phone/Windows Store App platform (won't talk much about this one, but this is the most convoluted painful integration of using .NET due to the platform restrictions and quite cumbersome to maintain for Unity)

As you can imagine the machinery to build a Unity platform is quite a burden (and sometimes it does add up OS platforms x .NET platforms x Graphics API!).

The core experience with .NET in Unity has been brought untiringly by Mono for many years and for several reasons:

- This was the only "OSS" runtime that Unity could license back in the days

- The Mono runtime is relatively easy to port to other platforms. Its overall simple C design implementation makes it easy to work with.

- As Unity was using an older version of Mono, including the boehm GC, It has been built around this "constraint", which strictly speaking, was actually imposing less constraints to the developers of the Unity Runtime

Though, If you are not familiar with Unity, Unity has a very different way of running .NET code compare to a traditional .NET app, so let me explain a bit more how this is roughly working.

How Unity is currently running your .NET code?

The engine is built around a simplified Entity-Component system, (currently being rebuilt from the ground up, more on that later), which is basically a way to favor composition over inheritance. An Entity (GameObject in Unity) doesn't hold any data directly and is not inheritable but is extensible through components (Component in Unity) that can be attached to it. There are several types of components, lots of them provided by the engine that are handled by some internal GameObject systems, but there are also end-user components (MonoBehavior Unity Scripts) that the engine will call directly.

But mostly, a large part of the engine is primarily built in C++, C# being at the edge of the end-user experience through the usage of C# Scripts. So when the engine has to process the C# GameObjects and Components, it will iterate them from C++ (they are entirely accessible from C++, including even fields access). If you check the call stack it will be only composed only of C++ code before it will reach a MonoBehavior method (e.g start, update)

These calls transitions from C++ to C# are costly, as arguments have to be "transpiled" from C++ to the way the .NET runtime is expecting them on the stack or registers. I haven't looked in the very details how Mono manage this transition there, but in .NET CLR, this is costly as well, as the runtime has to inform the GC about this transition, the GC has to know where to start to look into the stack for GC stack roots (Managed objects on the stack hold by C# code), perform a transition from preemptive GC to cooperative GC (Mono is different there, more on that later) and then call your method.

That's a reason why a few more advanced users of Unity have been already transferring these calls directly in C# by updating their objects from C# instead of letting the engine doing this less efficiently for them.

You can see now the difference with a regular .NET application where the C++ runtime is bootstrapped at the startup, but is quickly jumping into your C# Program.Main() method. So basically, the Unity Runtime is doing this jump several time, not just once (though sure, the first jump is more costly than the subsequent calls if you remove JIT time...etc.)

The IL2CPP AOT .NET Runtime

Unity has been providing for a few years now a tool-chain to convert IL to C++ at compile time and run your whole program in C++ instead with a dedicated .NET IL2CPP runtime. It was primarily done for supporting the changes in iOS AppStore, and It was somewhat done at a similar time where MetroApps/WindowsPhone/UWP was doing a similar work on the .NET runtime...

As you can imagine, the transitions from C++ to C# can be mitigated by the fact that there is no JIT in the middle and you can streamline a bit more easily the method calls, back (from C++ to .NET) and forth (e.g DllImport, internal calls), though it is still costly, specially if you need to work closely with the GC... but currently, IL2CPP is still relying on Boehm GC, so it has been less a problem until recently...

But even when running with IL2CPP, the Unity Engine C++ runtime sees the .NET objects still as scripting objects that are going through the same player loop, internal systems before calling your .NET Game scripts.

Moving to more C#!

If you have been working with C# and you know C++ as well, you understand the pros and cons of both language - and runtime. It is well accepted that moving to C# should increase your productivity for developing a game (it doesn't mean that it will always provide this, until you have to fight with some codegen/GC performance problems!) and that iteration during development time is critical, but the performance aspect of it has been increasingly important over the years as well, specially on mobile but also for more advanced games in Unity.

I have been always pushing over the years about performance in C#, and when I joined Unity 1.5 years ago, I was happy to discover that this direction of investing on C# was becoming more critical, by starting to move more engine parts to C# (e.g The scriptable render pipeline) and that performance was taken very seriously to push the limits and unleash more CPU for your games...

So to forge more performance into C#, we have been working for around one year on a new compiler technology called burst that will translate a subset of the C#/IL language to highly efficient native code (using LLVM as a main backend), along other highly connected work like the Job System and the new Entity Component System, all of this in order to be able to develop entirely in C#, games that could run faster than regular C++... though, this blog post is not about this technology, so I promise, I hope to post soon to unveil more about what we have been working on!

But while using a subset of C# for the critical part of your game is great, not being able to easily use simple objects like string or whatever managed objects coming from any .NET libraries out there in your game for less critical part is not really realistic... While we are building a path to provide good practice for data oriented programming in C#, we still want you to be able to use the regular .NET framework elsewhere in your game, in the many common cases where it makes sense and it is easier to deal with.

Though, this move to more C# doesn't mean that we would have to live in a schizophrenic world with a very fast C# subset on one side and a very slow full C# in the other...

So this is where porting Unity to CoreCLR (and later CoreRT) is going to lower the gap between between this two execution systems...

Why .NET CoreCLR for Unity?

The .NET Core Runtime aka CoreCLR is the cross-platform OSS .NET runtime, that has been released with a very permissive MIT license by Microsoft around 3 years ago in early 2015. Large part of its implementation were coming from the well established .NET Desktop Runtime (the one that has been shipped by default with Windows for years), including the JIT, the GC and base .NET types.

I would like to emphasis three main aspects on why CoreCLR could be important for Unity game developers:

- Performance is probably the main reason and I will detail why below

- Community is another aspect, related to performance, but not only

- Convergence/Evolution betting on the future

Performance with CoreCLR

There can be quite large difference in performance between different .NET runtime. That's the main reason why CoreCLR could be great for Unity game developers, as it will provide a significant boost in performance, by an order of 2x to 5x compare to the Mono runtime sometimes up to x10 on some workload! I'm pretty sure that many Unity developers would be very happy to get this boost without having to change a single line of code in their game...

What about IL2CPP? IL2CPP has been already providing quite significant performance improvements as well. Though on many benchmarks (on Windows MSVC, though Clang should be overall better), you will notice that the performance, on average, is still behind by a factor of 2x to .NET CoreCLR. You may wonder why, as the generated code is in C++?

The first reason is that IL2CPP team has been hard working on porting IL2CPP to more platforms and expanding the capabilities of using new C# compiler/language features for Unity Scripts, so they didn't have a chance to take the time to optimize more carefully the codegen and runtime, so it means that there is still room for improvements!

GC Aware Codegen

A more critical reason is the type of GC used and how well it is integrated with the codegen, the whole together can have a large performance impact on your application. As I said earlier, the Unity Engine has been relying on the Boehm Garbage Collector (even if there is some on going work to move to Mono SGen, more on that just below). Even though Boehm GC claims to have an incremental/generational GC, whenever I tested it against a .NET GC, it was falling way behind.

So, in order for a GC to be really efficient with the codegen, it is usually using what is called a young generation where newly allocated objects are stored. It is much faster to allocate within this young generation, because it is only a matter of advancing a pointer in memory instead of going through more complicated allocation patterns (e.g a free list to scan - as for example C++ malloc is often working). When this young collection is full, the GC will stop the threads and identify the objects to move from gen0 to gen1. How is this working? By using write barriers, a small code that is executed whenever you store a reference of an object into another field object (or to a static field) and that will record that you may have store a reference of a gen0 object to an older gen1/gen2 object. In order to be able to move these objects to an older collection, the GC will have to copy the data to another memory location and to update the pointers that were referencing these gen0 objects.

Obviously, lots of reference to these gen0 objects can come from the stack, so even when the GC is doing this small gen0 collection, it has to go through the stack to collect the gen0 object references, called stack roots. This is where it gets impossible for a C++ codegen to fight against a GC aware codegen, mainly because a GC aware codegen knows exactly where are these GC references at almost any point in the code (though usually, you use what is called stack maps at well know points to reduce the number of places where you need this information). Not only the GC is able to track these object references on the stack but it is also often able to do this on registers directly! When a GC has a precise information of the stack roots, it can quickly iterate on these stack root memory locations, and update these managed references.

But with a non aware GC codegen, you can't update stack roots like this because you don't know exactly where they are. So instead, non aware GC codegen has to use what is called a "conservative GC for stack roots". Typically, the GC will have to scan the whole stack memory (not only the stack roots), on every pointer size (usually aligned, so it can iterate on a pointer size) and try to determine if a particular memory location could be a reference to a managed object. The "could be" is where it gets difficult and dirty: usually, the GC has to compare a upper/lower bound of a memory to check if an object reference belongs to some GC owned memory. So what's the problem, we get the reference too no?

Well not exactly, and this is something I would like to explain more deeply because I have seen many false claims on Internet about this. What we are getting with this upper/lower bound checks is only a boolean that indicates whether the pointer might be a reference to a managed object, or... inside an object, or maybe outside of it (so it is not a managed object), but we don't know yet. We just have a coarse result of "yeah, maybe a managed object reference, or an interior pointer... but may be not" Because this sole information is not necessary for the GC to proceed: The GC will need later to go through the indirect references that this managed object has. But if you don't know where is exactly the beginning of this object, it gets impossible to do this at this granularity (and yes, you can have a system that track this at a finer level, but not sure it has ever been used in real GC production)

So in order to track these objects, quite often, the GC has a rough estimate, a range of GC memory that it should lock. Locking a range of memory means that it doesn't know exactly where the object is, plus the reason is that a reference on the stack could be a perfectly valid data that is actually not a managed object reference, so the GC can't update the pointers in the end. But it still has to make sure that it will not collect these objects. So in the end, what's happening is that the gen0 can be actually not collected by a conservative GC. Instead, the GC will keep this region of memory (with intermediate collectable objects that could be collected but are not because they may be intermixed with gen0-to-gen1 objects candidates) and it will continue increasing the gen0 memory.

Sorry for this long digression, that I will try to summarize through a few points:

- A non aware GC codegen is usually forced to use a conservative GC

- A conservative GC is... conservative so most of the time breaking the promise of generational collections:

- It can't move objects around that are on the stack because its is not safe, meaning that it can't move gen0 objects to older gen

- If some objects are identified as potentially gen0 objects, it will have to keep a block of memory (and not only the selected pointers, because, it doesn't know exactly where the objects are... without an expensive lookup), meaning that it will keep even objects that could be collected .Though this can be mitigated by re-scanning the entire gen0 and computing a proper lower/upper bound on every object and compare them with the reference objects... but I'm not sure this is sustainable and don't know if .NET GC is doing something more advanced here, as the conservative GC is not production-able, but mostly provide an easy workaround when it is not yet ported. For gen1/gen2, it is more likely valid as well.

- As some objects in gen0 collection can be "locked" (or "pinned") by this conservative scan, it will have to continue bumping the gen0 pointer (or use another bump buffer) after the last object being locked (or the region if the GC is not able to detect this)

- You are loosing the promise of object compaction, which is another benefit of a generational GC, meaning less efficient data locality for your managed objects (intermixed with data that is no longer used), meaning more cache trashing, more cache misses...etc.

That's why a GC aware codegen like the CoreCLR RyuJIT being able to play nice with the GC will ultimately run faster, with a more efficient usage of memory.

Codegen breakthrough

Another important aspect since CoreCLR has been OSS is the constant work from top Microsoft JIT/GC engineers (and the community, more about that after) that have been put into optimizing JIT code to the point where in many cases, the codegen is as good as what you could get with C++

Example of performance improvements:

- Runtime optimizations related to

Span<T>andReadOnlySpan<T> - Recently they have been bringing Tiered JIT Compilation, which will bring opportunities to both 1) improve throughput of JIT code by generating slightly less efficient code and 2) by optimizing more methods based on usage. See this in-depth article about Tiered JIT compilation by Math Warren worth a read!

A quick look at some PR closed for codegen gives quite a good overview of the amount of work being pushed...

Debugging experience

This is one part that is often forgotten, but despite the incredible work done by Jb Evain at Microsoft to provide a great debugging experience with Mono and Unity, it is also true that the .NET debugger, profiling and instrumentation infrastructure (Windbg SOS, integration with PerfView...etc.), ability to have a mixed C++/C# debugger (something I'm using daily), years of great experience available easily...

One little fact for example in the Unity Editor related to this: In order to allow game developers to attach easily a C# debugger to the Unity Editor, there is an option in File/Project Settings to allow the debugger to attach to the Mono runtime that is on by default. This sole option is making the JIT code generated by Mono around 5x to 10x slower than the normal Mono JIT code, meaning that the Unity Editor, currently, is running somewhat around 10x to 50x slower than a solution that would be based on .NET CoreCLR... think about what you could do with this lost power on very large scene and game projects...

Community

Over the recent years, many external contributors have been able to improve the JIT and also the GC, while still more difficult to approach

But also, you will notice lots of work related to ARM32 and ARM64... and that's where the Community - including corporate work from Samsung for the Tizen platform - has been able to help a lot!

CoreCLR is one part of the runtime, but also many performance improvements have been made to the core .NET libraries, as for example Ben Adams long list of PR performance oriented to corefx

I really suggest you to have a look Open Source .NET – 3 years later by Matt Warren (again!). His blog post series show that we have not only people actively working on the .NET Runtime, but also other people contributing to the community, Matt Warren being a vibrant example of a technical performance-oriented observer of the .NET runtime over the past years!

Initiative like BenchmarkDotNet actively improved by Andrey Akinshin and Adam Sitnik are also notable example of people contributing indirectly to the performance challenges of CoreCLR.

Convergence and Evolution with CoreCLR

The undergoing work around CoreRT, the AOT solution for .NET (while CoreCLR provides a JIT) is also very promising.

First, one of the backend is leveraging the CoreCLR RyuJIT GC aware codegen, meaning that we can get a very efficient AOT code that is working cooperatively with the GC.

Secondly, because there was also lots of work done on LLILC, a LLVM JIT/AOT backend, though unfortunately, the work has been stopped two years ago, but they were re-affected to improve back CoreCLR, so in the end, that was not that a bad choice. I hope that these codegen-gurus will be able to work back on LLILC.

Lastly because CoreRT is aligned with Unity vision of more code in C# and a very small runtime in C++, see for example this comment from Michal Strehovsky about CoreRT usages, fascinating to see that it could even be used as a foundation for some prototype OS

If you think about Unity as a Platform, not only as an engine, but with a full developer and game platform - from the core engine, the ad services, the machine learning parts...etc. - CoreRT could be part of this picture, by providing the core foundation of a lightweight runtime...

So, let's see how we were able to integrate CoreCLR to Unity... I'm worried that this post is getting too long... I hope that I will not squash too much the following parts that might have more interests for you!

How CoreCLR was integrated to Unity?

It all started during the Christmas period in December 2016, before that I had a few discussions with some technical fellow at Unity that were pointing that it might be a huge task to try to run CoreCLR in Unity... but knowing a bit how the underlying things are glue together in this domain (both at mono and CoreCLR side), I was more optimistic... (though I'm not minoring the fact that It will require *lots* of work!).

So during my holidays, I started to work on this PR [WIP] Collectible Assemblies and AssemblyLoadContext. What's the link with Unity? Because I originally wanted to challenge the most difficult part, related to the Unity Editor that is using AppDomains to reload the entire game assemblies. As CoreCLR has dropped support for AppDomains (which I really agree with), there was quite some work to bring a similar feature to life (i.e. Collectible Assemblies), so I challenged myself to enter the CoreCLR codebase from this side.

I also started to roughly prototype how I would make this integration. The idea was pretty simple: As Mono is a very approachable C API (I would love to see this kind of easy API in CoreCLR - as it is one of the negative point) that is exported to a shared library runtime, the idea is simply to provide this exact same Mono C API but by providing a full implementation based on CoreCLR.

After a few days of work, I had collectible assemblies working quite well, but along the route, I discovered that I would have to develop also other critical parts (like DllImport not supported in Collectible Assemblies, or the inefficiency of static variables in Collectible Assemblies...etc.), and that was way beyond what I wanted to do for a prototype... (and my spare-time is really precious, as everybody here right?) so I decided to put this idea on a hold... just to receive a few weeks later an invitation to the Unity HackWeek, and I immediately thought that it would be a fantastic opportunity to challenge this idea and be able to work for a full week on this with few other folks to help!

Hackweek came around May 2017, but since December, quite a few things happened in the meantime for .NET CoreCLR. Specifically a preview CoreCLR 2.0 was released and with the good experience I had already with netstandard1.6, I was pretty confident that it would secure a lot more the problems of compiling Unity with this new surface API. I was also lucky to be able to use the 2.0 preview that was released a few weeks just before the HackWeek, as it enabled us to use plain nuget packages with a custom CoreCLR compiled. Due to my experience with implementing Collectible Assemblies which was quite painful because of the convoluted building process between CoreCLR and CoreFX, I didn't want to have to face these build limitation issues.

The overall plan for the week

First, was to focus only on the StandalonePlayer, not the Unity Editor. It simplified the missing AppDomains and it likely narrowed down the number of Mono API we had to implement. So the overall goal was to run a very simple scene, with just a cube rotating on the screen, and in order to get there, we wanted to:

- Develop a simple program using Mono runtime hosting API to load a class, and invoke a static method on it, used as a very simple Mono Hosting HelloWorld program

- In the meantime, develop the relevant API used by this simple program on top of CoreCLR

- Once we got something working with CoreCLR, start developing the missing APIs

- We also had the task to compile the UnityEngine managed assembly with

netcoreapp2.0and this could be done in // of implementing the mono C functions, so one person was able to work concurrently on this.

Narrow down the scope

In order to narrow down the number of functions to implement (there are more than 200+ used in Unity), I developed a very thin mono proxy dll that could imitate the whole mono API and redirect to the real Mono runtime, while logging all the calls to a file. It helped a lot to lower the number of functions down to 88! Which was a lot more manageable than the 200+ functions in the API.

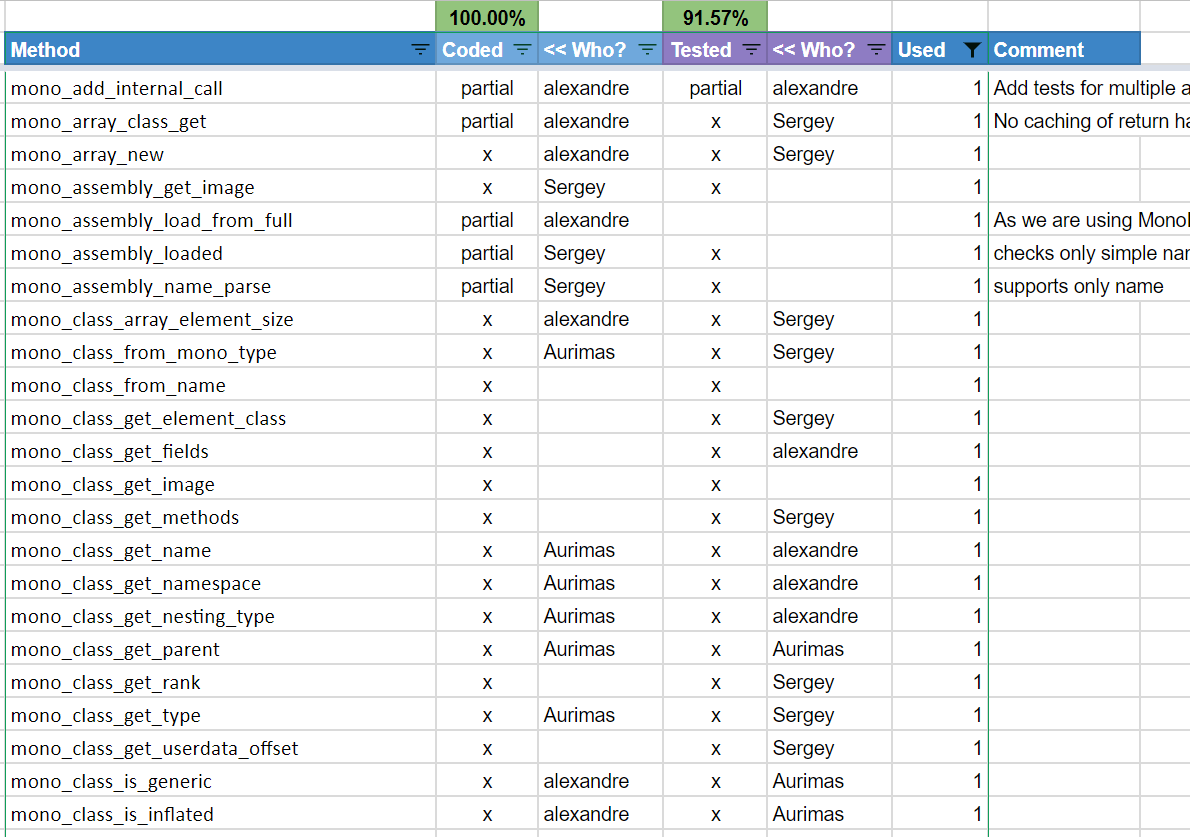

With this list, it was also much easier to dispatch our work. With a shared spreadsheet online, we had this list of functions to implement and 2-3 of us started to implement them:

Exposing CoreCLR as a Mono API

We developed the entire Mono extension within a fork of CoreCLR (in a private repository).

The idea was to integrate directly as part of the coreclr.dll the Mono API exposed functions and to call the internals of CoreCLR. Using this mode of development made the whole experience a lot more easier to work with, as we had also to modify a few parts in CoreCLR as well.

1) Develop a simple Mono HelloWorld program

int main()

{

auto assembly = mono_domain_assembly_open (domain, "coreclrtest.dll");

MonoImage* image = mono_assembly_get_image(assembly);

MonoClass* klass = mono_class_from_name(image, "coreclrtest", "test");

MonoMethodDesc* methodDesc = mono_method_desc_new ("GetNumber", false);

MonoMethod* method = mono_method_desc_search_in_class (methodDesc, klass);

MonoObject* returnValue = mono_runtime_invoke(method, nullptr, nullptr, nullptr);

int int_result = *(int*)mono_object_unbox (returnValue);

printf("Invoke result: %i\n", int_result);

//mono_jit_cleanup (domain);

return 0;

}

2) Implement the Mono API

we had a single file inside coreclr/src/vm/mono/mono_coreclr.cpp that was implementing the whole Mono API.

Typically, the function mono_domain_assembly_open was implemented like this:

extern "C" MonoAssembly * mono_domain_assembly_open(MonoDomain *domain, const char *name)

{

CONTRACTL

{

THROWS;

GC_TRIGGERS;

// We don't support multiple domains

PRECONDITION(domain == g_RootDomain);

PRECONDITION(domain != nullptr);

PRECONDITION(name != nullptr);

}

CONTRACTL_END;

SString assemblyPath(SString::Utf8, name);

auto domain_clr = (MonoDomain_clr*)domain;

auto assembly = AssemblySpec::LoadAssembly(assemblyPath.GetUnicode());

assembly->EnsureActive();

//auto domainAssembly = assembly->GetDomainAssembly((MonoDomain_clr*)domain);

return (MonoAssembly*)assembly;

}

As you can see a Mono call is mostly going to be just one or a few calls to the CoreCLR API, so that was very manageable!

You can notice also that I tried to enforce usage of the CONTRACTL/CONTRACTL_END as it is used in CoreCLR to make sure that we didn't break some invariants (like switching from GC Preemptive to Cooperative, more on that later), as I tried to follow most of the recommendations from the fantastic Book of the Runtime in CoreCLR

So we had still a long way to go (88 methods!). On our way we discovered how basically to use CoreCLR runtime to map it to the Mono API, that was really a full discovery process, sometimes quite laborious, as it was not obvious how to map certain behavior. We were not entirely sure that we could get stuck completely in our way!

We started also to improve our sample HelloWorld program by adding a lot more tests and method. We didn't take the time to add a nice C++ gtests workflow, so we were just using a plain main program... that was not completely ideal, as we get caught by some regressions not carefully tracked by our main test program, but it was still not that bad to be able to iterate quickly on a big main test program...

3) Changing the CoreCLR Runtime

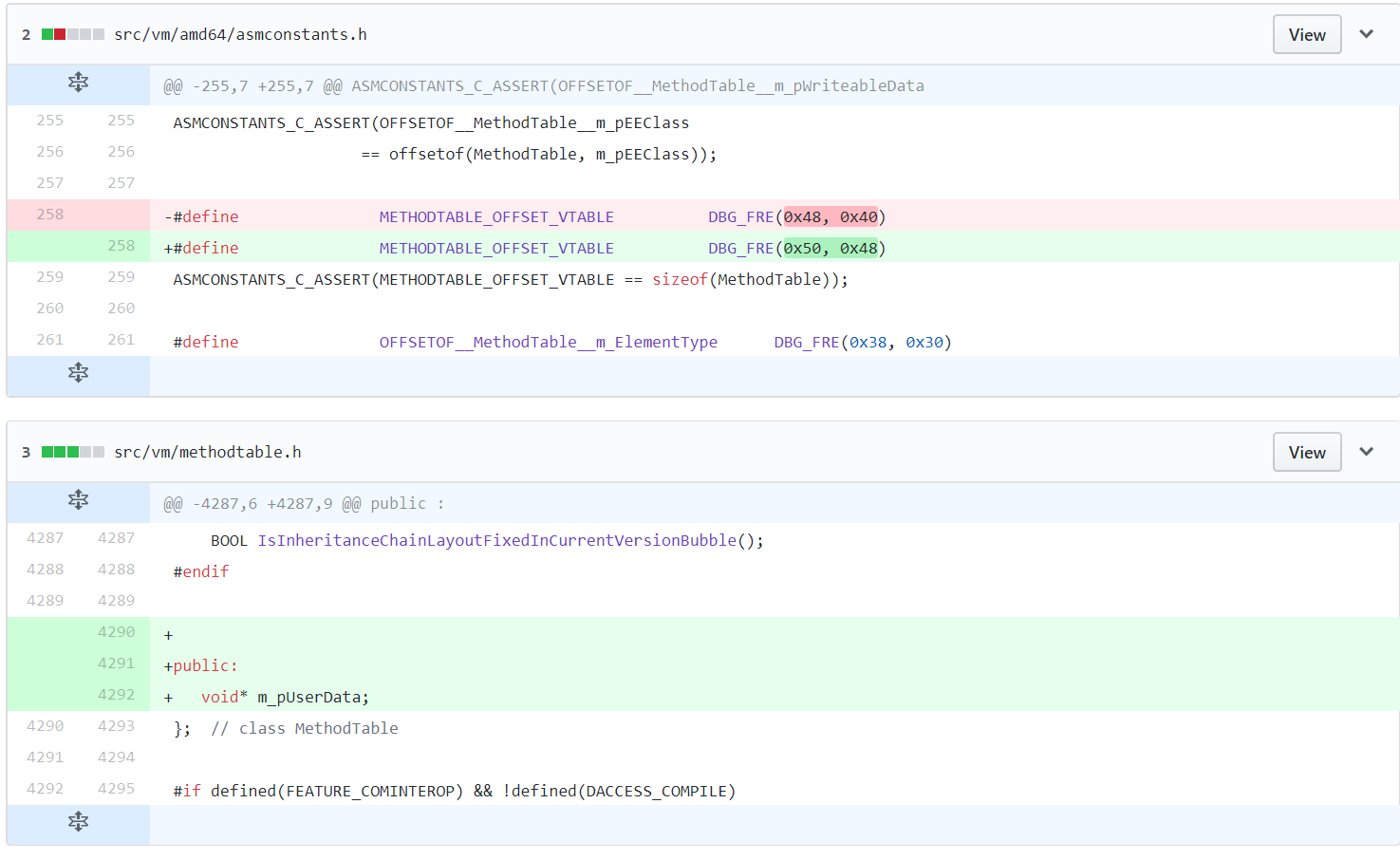

We had to change few parts in CoreCLR to match what were possible to do with Mono. You can see following an extract of a few of these changes:

- Typically, It was possible to store in Mono a userdata pointer in the MethodTable (the equivalent of the VTABLE + Type descriptor)

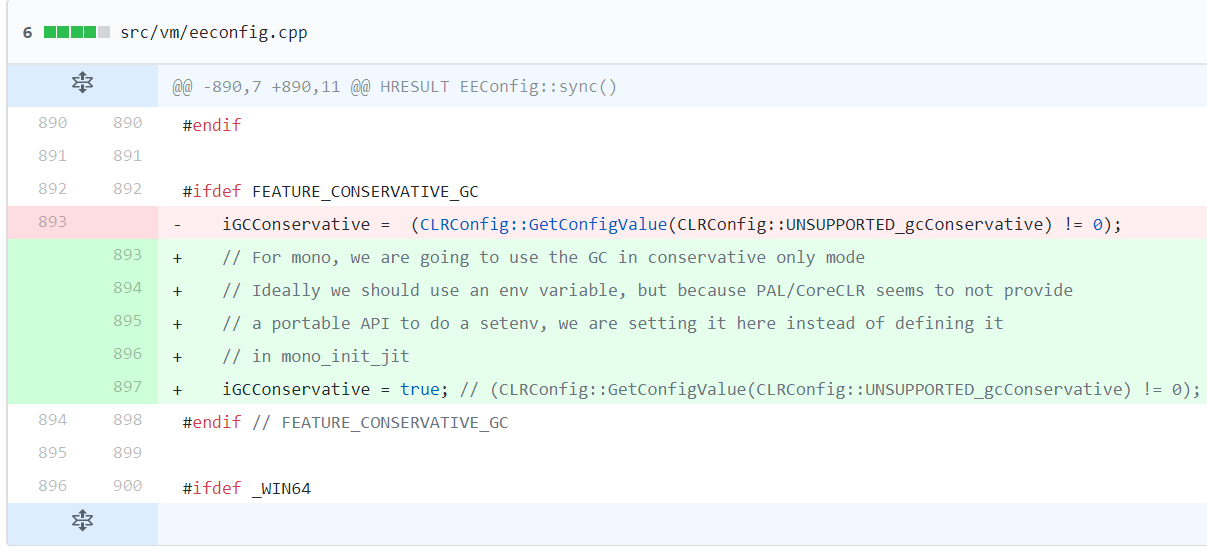

- Another one was to switch the CoreCLR GC to perform conservative stack scanning (as the Unity C++ runtime is currently not designed with this in mind, though the IL2CPP team has been recently working on correcting this!)

- Add support for registration of iCalls (internal calls)

This part was probably the trickiest part of the changes - while in the end a very small change, as with Mono, you have the possibility to register Internal calls, dynamically at runtime. While most of the API in CoreCLR is done in src/vm/ecall.cpp, all the internal calls are actually registered from a static table. So the changes were added to add support for dynamic registration (at runtime) as it is supported by Mono.

In CoreCLR, you have roughly two types of internal calls, FCall and QCall. This is well described in the documentation of CoreCLR Mscorlib and Calling Into the Runtime.

Because of the nature of the iCall in Mono, we had to use FCall in CoreCLR, which are basically calls that are running in Cooperative mode (same as the calling C# code in fact)

This is where it gets ugly and you really need to read the documentation "What Every CLR Developer Must Know Before Writing Code" to understand how to use this FCall.

This is where you need to be super careful to not introduce GC holes and make sure that your C++ code is GC Safe...

Overall we started on the Monday 22th May and we were able to complete all the functions only 4 days later on the 25th, 160 commits later, that was amazing to get to that point!

Changes to Unity

The changes to the Unity runtime were surprisingly very minor, but the truth is that we didn't make the full set of changes really required to make it working correctly with CoreCLR in the long run (mainly changing all the existing code accessing directly managed fields from C++ when storing managed references and use proper write barriers instead). So we were lucky in the end that everything was running without having to patch the entire Unity codebase!

The main change was to modify the offset to the first field of Managed Objects when accessing them from C++, as Unity was using some a fixed value bound to the way Mono had layout its object.

The second, sneaky change, was related to some C++ code accessing the field of a managed class from mscorlib directly with a hardcoded pointer offset. The details of implementation of mscorlib (e.g private fields of System.MulticastDelegate for example) are largely varying between .NET runtime, so we had to be careful about this kind of access, but fortunately, we had only one or two places to fix this in Unity to proceed further. Though it took quite some time to find this illegal access (basically resulting in a NullReferenceException on an unrelated managed object)

But we were all so excited to get to this screen with a happy spinning cube in the middle:

What's next?

I wish I could have given a lot more details in this blog post, but trying to recall exactly what we did 9 months ago was a lot more difficult than I thought. My apologize for postponing this feedback work.

But, hey, at least it gives a glimpse of the future! :)

Another glimpse of the future that will come much before CoreCLR is our work on the new burst compiler technology to unleash SIMD with data oriented programming performance to C#.

I will give a lot more details about it in an upcoming blog post, hopefully you will not wait 9 months to enjoy reading it!

If you can't wait, you should have a look at the talk that Andreas Fredickson gave at GDC 2018 about C# to Machine Code that gives a few hints about our work:

Also I recommend you to watch Mike Acton GDC 2018 presentation about "Democratizing Data-Oriented Design: A Data-Oriented Approach to Using Component Systems" which gives insights about how Unity is going to help you design efficient data-oriented programming game

Happy coding!